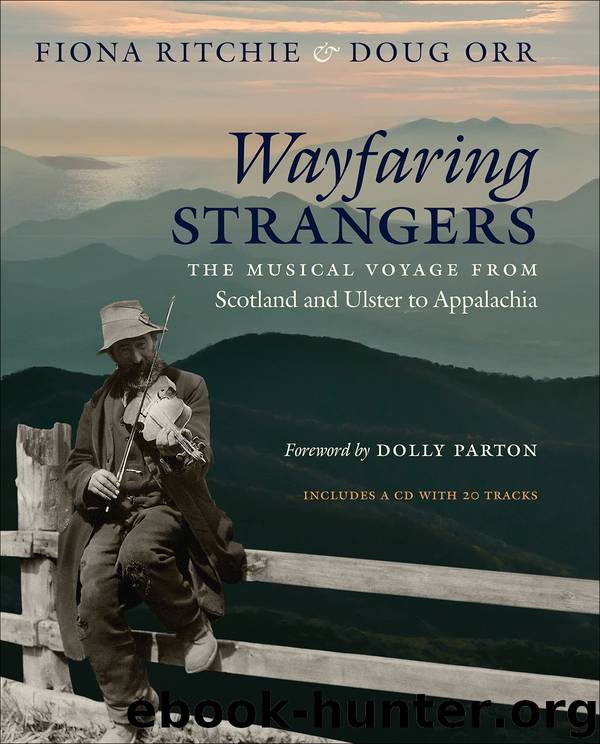

Wayfaring Strangers by Ritchie Fiona Orr Doug Orr Darcy

Author:Ritchie, Fiona, Orr, Doug, Orr, Darcy

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2014-01-29T05:00:00+00:00

[Chorus] Shady Grove my little love Shady Grove I say,

Shady Grove my little love I’m bound to go away.

Now when I was a little boy I wanted a barlow knife,

Now I want little Shady Grove to say she’ll be my wife.

A kiss from little Shady Grove as sweet as brandy wine,

Ain’t no girl in this whole world is prettier than mine.

The old ballads were traditionally sung in the Appalachians by a solo singer a capella (or “Acapulco” as Sheila Kay Adams’s Granny called it13). Instrumentation might be added later, but many continued the sean-nós singing style from Ulster and unaccompanied Scottish ballad delivery, performing in a detached manner devoid of drama even though the ballad lyrics might be extremely graphic and emotional. Mountain singers, like their ancestors, had a deep respect for the songs, and while they may have been affected by their stories, they would not tamper with tempo and volume, nor add theatrical gestures. It underscored the communally held philosophy that traditional singing was not about the singer and the performance. The old ballad stories were owned by no one and yet by everyone: generations of singing families and communities. The singer’s job was to give the song a voice.

Appalachian ballad lyrics and melodies tended to be mournful in tone, which kept faith with a legacy of toil and struggle, parting and loss. (Modal chords in a minor key were common.) They resonated with the misfortunes and migrations of the centuries, shadows of life from an amalgamation of experiences: repressive rulers, deprivations, families and loves left or lost, perils of oceanic migration, struggles of strangers in a strange land, the fear of foreboding landscapes. Scottish folklorist and ballad singer Margaret Bennett notes that the Scots Gaelic language has expressions of mournfulness without equivalent in English.14 Cecil Sharp’s collecting colleague Maud Karpeles, who recorded the song words, found Appalachian melodies to be even more “austere” than their Old World counterparts.15 Little wonder that the eventual merging of the Old World singing and sorrowful Appalachian balladry would produce the “high lonesome sound,” a defining characteristic of bluegrass and old-time music. Yet soaring above the soulful nature of many of the ballads is an air of resilience and human perseverance, an essential life spirit filled with love as well as sorrow. Ulster-born singer and guitarist Dáithí Sproule of the Irish group Altan highlights the native Gaelic traditions of Donegal in his repertoire. Introducing them to American audiences, he often remarks that, although most of the songs he sings are sad, they fill him with an abiding feeling of love. Perhaps this is also why Sheila Kay Adams’s Granny called them all simply “love songs.” Sheila Kay recalls: “Didn’t make any difference how much killing, murdering, or . . . you know, the ballads, the old ballads, the story songs, she referred to ‘em all as love songs.”16

The Appalachian ballad singers also preserved another Old World tradition: the intermingling of songs with storytelling. In fact, ballads in the early days were often referred to as “story songs.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Aircraft Design of WWII: A Sketchbook by Lockheed Aircraft Corporation(32187)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31246)

Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman(20347)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18802)

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18500)

Shoot Sexy by Ryan Armbrust(17633)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17313)

Portrait Mastery in Black & White: Learn the Signature Style of a Legendary Photographer by Tim Kelly(16931)

Adobe Camera Raw For Digital Photographers Only by Rob Sheppard(16880)

Photographically Speaking: A Deeper Look at Creating Stronger Images (Eva Spring's Library) by David duChemin(16596)

Ready Player One by Cline Ernest(14488)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14308)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13949)

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13453)

Art Nude Photography Explained: How to Photograph and Understand Great Art Nude Images by Simon Walden(12950)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11705)

The Priory of the Orange Tree by Samantha Shannon(8848)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8784)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8762)